Critical appraisal of meta-analysis.

Guidelines for critical reading of a meta-analysis are proposed. The main points dealt with by the PRISMA declaration are also described.

Yes, I know that the saying goes just the opposite. But that is precisely the problem we have with so much new information technology. Today anyone can write and make public what goes through his head, reaching a lot of people, although what he says is bullshit (and no, I do not take this personally, not even my brother-in-law reads what I post!).

The problem is that much of what is written is not worth a bit, not to refer to any type of excreta. There is a lot of smoke and little fire, when we all would like the opposite to happen.

The same happens in medicine when we need information to make some of our clinical decisions. Anywhere the source we go, the volume of information will not only overwhelm us, but above all the majority of it will not serve us at all. Also, even if we find a well-done article it may not be enough to answer our question completely. That’s why we love so much the revisions of literature that some generous souls publish in medical journals.

They save us the task of reviewing a lot of articles and summarizing the conclusions. Great, isn’t it? Well, sometimes it is, sometimes it is not. As when we read any type of medical literature’s study, we should always make a critical appraisal and not rely solely on the good know-how of its authors.

Revisions, of which we already know there are two types, also have their limitations, which we must know how to value. The simplest form of revision, our favorite when we are younger and ignorant, is what is known as a narrative review or author’s review. This type of review is usually done by an expert in the topic, who reviews the literature and analyzes what she finds as she believes that it is worth (for that she is an expert) and summarizes the qualitative synthesis with her expert’s conclusions.

These types of reviews are good for getting a general idea about a topic, but they do not usually serve to answer specific questions. In addition, since it is not specified how the information search is done, we cannot reproduce it or verify that it includes everything important that has been written on the subject. With these revisions we can do little critical appraising, since there is no precise systematization of how these summaries have to be prepared, so we will have to trust unreliable aspects such as the prestige of the author or the impact of the journal where it is published.

As our knowledge of the general aspects of science increases, our interest is shifting towards other types of revisions that provide us with more specific information about aspects that escape our increasingly wide knowledge. This other type of review is the so-called systematic review (SR), which focuses on a specific question, follows a clearly specified methodology of searching and selection of information and performs a rigorous and critical analysis of the results found.

Moreover, when the primary studies are sufficiently homogeneous, the SR goes beyond the qualitative synthesis, also performing a quantitative synthesis analysis, which has the nice name of meta-analysis. With these reviews we can do a critical appraising following an ordered and pre-established methodology, in a similar way as we do with other types of studies.

The prototype of SR is the one made by the Cochrane’s Collaboration, which has developed a specific methodology that you can consult in the manuals available on its website. But, if you want my advice, do not trust even the Cochrane’s and make a careful critical appraising even if the review has been done by them, not taking it for granted simply because of its origin. As one of my teachers in these disciplines says (I’m sure he’s smiling if he’s reading these lines), there is life after Cochrane’s. And, besides, there is lot of it, and good, I would add.

Critical appraisal of meta-analyes

Although SRs and meta-analyzes impose a bit of respect at the beginning, do not worry, they can be critically evaluated in a simple way considering the main aspects of their methodology. And to do it, nothing better than to systematically review our three pillars: validity, relevance and applicability.

Regarding VALIDITY, we will try to determine whether or not the revision gives us some unbiased results and respond correctly to the question posed. As always, we will look for some primary validity criteria. If these are not fulfilled we will think if it is already time to walk the dog: we probably make better use of the time.

Has the aim of the review been clearly stated? All SRs should try to answer a specific question that is relevant from the clinical point of view, and that usually arises following the PICO scheme of a structured clinical question. It is preferable that the review try to answer only one question, since if it tries to respond to several ones there is a risk of not responding adequately to any of them. This question will also determine the type of studies that the review should include, so we must assess whether the appropriate type has been included.

Although the most common is to find SRs of clinical trials, they can include other types of observational studies, diagnostic tests, etc. The authors of the review must specify the criteria for inclusion and exclusion of the studies, in addition to considering their aspects regarding the scope of realization, study groups, results, etc. Differences among the studies included in terms of (P) patients, (I) intervention or (O) outcomes make two SRs that ask the same question to reach to different conclusions.

If the answer to the two previous questions is affirmative, we will consider the secondary criteria and leave the dog’s walk for later.

Have important studies that have to do with the subject been included? We must verify that a global and unbiased search of the literature has been carried out. It is frequent to do the electronic search including the most important databases (generally PubMed, Embase and the Cochrane’s Library), but this must be completed with a search strategy in other media to look for other works (references of the articles found, contact with well-known researchers, pharmaceutical industry, national and international registries, etc.), including the so-called gray literature (thesis, reports, etc.), since there may be important unpublished works.

And that no one be surprised about the latter: it has been proven that the studies that obtain negative conclusions have more risk of not being published, so they do not appear in the SR. We must verify that the authors have ruled out the possibility of this publication bias. In general, this entire selection process is usually captured in a flow diagram that shows the evolution of all the studies assessed in the SR.

It is very important that enough has been done to assess the quality of the studies, looking for the existence of possible biases. For this, the authors can use an ad hoc designed tool or, more usually, resort to one that is already recognized and validated, such as the bias detection tool of the Cochrane’s Collaboration, in the case of reviews of clinical trials.

This tool assesses five criteria of the primary studies to determine their risk of bias: adequate randomization sequence (prevents selection bias), adequate masking (prevents biases of realization and detection, both information biases), concealment of allocation (prevents selection bias), losses to follow-up (prevents attrition bias) and selective data information (prevents information bias). The studies are classified as high, low or indeterminate risk of bias according to the most important aspects of the design’s methodology (clinical trials in this case).

In addition, this must be done independently by two authors and, ideally, without knowing the authors of the study or the journals where the primary studies of the review were published. Finally, it should be recorded the degree of agreement between the two reviewers and what they did if they did not agree (the most common is to resort to a third party, which will probably be the boss of both).

To conclude with the internal or methodological validity, in case the results of the studies have been combined to draw common conclusions with a meta-analysis, we must ask ourselves if it was reasonable to combine the results of the primary studies. It is fundamental, in order to draw conclusions from combined data, that the studies are homogeneous and that the differences among them are due solely to chance.

Although some variability of the studies increases the external validity of the conclusions, we cannot unify the data for the analysis if there are a lot of variability. There are numerous methods to assess the homogeneity about which we are not going to refer now, but we are going to insist on the need for the authors of the review to have studied it adequately.

In summary, the fundamental aspects that we will have to analyze to assess the validity of a SR will be: 1) that the aims of the review are well defined in terms of population, intervention and measurement of the result; 2) that the bibliographic search has been exhaustive; 3) that the criteria for inclusion and exclusion of primary studies in the review have been adequate; and 4) that the internal or methodological validity of the included studies has also been verified.

In addition, if the SR includes a meta-analysis, we will review the methodological aspects that we saw in a previous post: the suitability of combining the studies to make a quantitative synthesis, the adequate evaluation of the heterogeneity of the primary studies and the use of a suitable mathematical model to combine the results of the primary studies (you know, that of the fixed effect and random effects models).

Regarding the RELEVANCE of the results we must consider what is the overall result of the review and if the interpretation has been made in a judicious manner.

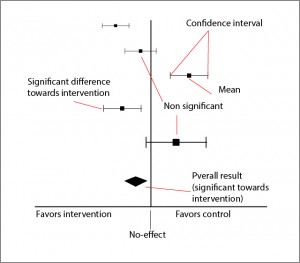

The SR should provide a global estimate of the effect of the intervention based on a weighted average of the included quality items. Most often, relative measures such as risk ratio or odds ratio are expressed, although ideally, they should be complemented with absolute measures such as absolute risk reduction or the number needed to treat (NNT). In addition, we must assess the accuracy of the results, for which we will use our beloved confidence intervals, which will give us an idea of the accuracy of the estimation of the true magnitude of the effect in the population.

As you can see, the way of assessing the importance of the results is practically the same as assessing the importance of the results of the primary studies. In this case we give examples of clinical trials, which is the type of study that we will see more frequently, but remember that there may be other types of studies that can better express the relevance of their results with other parameters. Of course, confidence intervals will always help us to assess the accuracy of the results.

Generally, the most powerful studies have narrower intervals and contribute more to the overall result, which is expressed as a diamond whose lateral ends represent its confidence interval. Only diamonds that do not cross the vertical line will have statistical significance. Also, the narrower the interval, the more accurate result. And, finally, the further away from the zero-effect line, the clearer the difference between the treatments or the comparative exposures will be.

If you want a more detailed explanation about the elements that make up a forest plot, you can go to the previous post where we explained it or to the online manuals of the Cochrane’s Collaboration.

We will conclude the critical appraising of the SR assessing the APPLICABILITY of the results to our environment. We will have to ask ourselves if we can apply the results to our patients and how they will influence the care we give them. We will have to see if the primary studies of the review describe the participants and if they resemble our patients. In addition, although we have already said that it is preferable that the SR is oriented to a specific question, it will be necessary to see if all the relevant results have been considered for the decision making in the problem under study, since sometimes it will be convenient to consider some other additional secondary variable.

And, as always, we must assess the benefit-cost-risk ratio. The fact that the conclusion of the SR seems valid does not mean that we have to apply it in a compulsory way.

If you want to correctly assess a SR without forgetting any aspect, you can help yourself with one of the tools used for its writing, such as the checklist such as PRISMA’s or some of the tools available on the Internet for critical appraisal, such as the grills that can be download from the CASP page, which are the ones we have used for everything we have said so far.

PRISMA statement

The PRISMA statement (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyzes) consists of 27 items, classified in 7 sections that refer to the sections of title, summary, introduction, methods, results, discussion and financing:

- Title: it must be identified as SR, meta-analysis or both. If it is specified, in addition, that it deals with clinical trials, priority will be given to other types of reviews.

- Summary: it should be a structured summary that should include background, objectives, data sources, inclusion criteria, limitations, conclusions and implications. The registration number of the revision must also be included.

- Introduction: includes two items, the justification of the study (what is known, controversies, etc) and the objectives (what question tries to answer in PICO terms of the structured clinical question).

- Methods. It is the section with the largest number of items (12):

– Protocol and registration: indicate the registration number and its availability.

– Eligibility criteria: justification of the characteristics of the studies and the search criteria used.

– Sources of information: describe the sources used and the last search date.

– Search: complete electronic search strategy, so that it can be reproduced.

– Selection of studies: specify the selection process and inclusion’s and exclusion’s criteria.

– Data extraction process: describe the methods used to extract the data from the primary studies.

– Data list: define the variables used.

– Risk of bias in primary studies: describe the method used and how it has been used in the synthesis of results.

– Summary measures: specify the main summary measures used.

– Results synthesis: describe the methods used to combine the results.

– Risk of bias between studies: describe biases that may affect cumulative evidence, such as publication bias.

– Additional analyzes: if additional methods are made (sensitivity, metaregression, etc) specify which were pre-specified.

- Results. Includes 7 items:

– Selection of studies: it is expressed through a flow chart that assesses the number of records in each stage (identification, screening, eligibility and inclusion).

– Characteristics of the studies: present the characteristics of the studies from which data were extracted and their bibliographic references.

– Risk of bias in the studies: communicate the risks in each study and any evaluation that is made about the bias in the results.

– Results of the individual studies: study data for each study or intervention group and estimation of the effect with their confidence interval. The ideal is to accompany it with a forest plot.

– Synthesis of the results: present the results of all the meta-analysis performed with the confidence intervals and the consistency measures.

– Risk of bias between the subjects: present any evaluation that is made of the risk of bias between the studies.

– Additional analyzes: if they have been carried out, provide the results of the same.

- Discussion. Includes 3 items:

– Summary of the evidence: summarize the main findings with the strength of the evidence of each main result and the relevance from the clinical point of view or of the main interest groups (care providers, users, health decision-makers, etc.).

– Limitations: discuss the limitations of the results, the studies and the review.

– Conclusions: general interpretation of the results in context with other evidences and their implications for future research.

- Financing: describe the sources of funding and the role they played in the realization of the SR.

As a third option to these two tools, you can also use the aforementioned Cochrane’s Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, available on its website and whose purpose is to help authors of Cochrane’s reviews to work explicitly and systematically.

We’re leaving…

As you can see, we have not talked practically anything about meta-analysis, with all its statistical techniques to assess homogeneity and its fixed and random effects models. And is that the meta-analysis is a beast that must be eaten separately, so we have already devoted two post only about it that you can check when you want. But that is another story…