Critical appraisal of economic valuations

We review the methodological aspects of the economic evaluation studies and general guidelines are given for the critical aprraisal of these documents.

Yes, as the illustrious Francisco de Quevedo y Villegas once said, powerful gentleman is Don Dinero (Mr. Money). A great truth because, who, purely in love, does not humble himself before the golden yellow? And even more in a mercantilist and materialist society like ours.

But the problem is not that we are materialistic and just think about money. The problem is that nobody believes they have all the money they need. Even the wealthiest would like to have much more money.

And many times, it is true, we do not have enough money to cover all our needs as we would like.

And that does not only happen at the individual’s level, but also at social groups level. Any country has a limited amount of money, which is why you cannot spend everything you want and you have to choose where you spend your money. Let’s think, for example, of our healthcare system, in which new health technologies (new treatments, new diagnostic techniques, etc. ) are getting better … and more expensive (sometimes, even bordering on obscenity).

If we are spending at the limit of our possibilities and want to apply a new treatment, we only have two choices: either we increase our wealth (where do we get the money from?) or we stop spending it on something else. There would be a third one that is used frequently, even if it is not the right thing to do: spend what we do not have and pass on the debt to whoever comes next.

Yes, my friends, the saying that Health is priceless does not hold up economically. Resources are always limited and we must all be aware of the so-called opportunity cost of a product: the price it costs, the money will have to stop spending on something else.

Therefore, it is very important to properly evaluate any new health technology before deciding its implementation in the health system, and this is why the so-called economic evaluation studies have been developed, aimed at identifying what actions should be prioritized to maximize the benefits produced in an environment with limited resources.

These studies are a tool to assist in decision-making, but are not aim to replace it, so other elements have to be taken into account, such as justice, equity and free access to the election.

Valuation economic studies

The economic evaluation (EV) studies encompass a whole series of methodology and specific terminology that is usually little known by those who are not dedicated to the evaluation of health technologies. Let’s briefly review its characteristics to finally give some recommendations on how to make a critical appraisal of these studies.

The first thing would be to explain what are the two characteristics that define an EV. These are the measure of the costs and benefits of the interventions (the first one) and the choice or comparison between two or more alternatives (the second one).

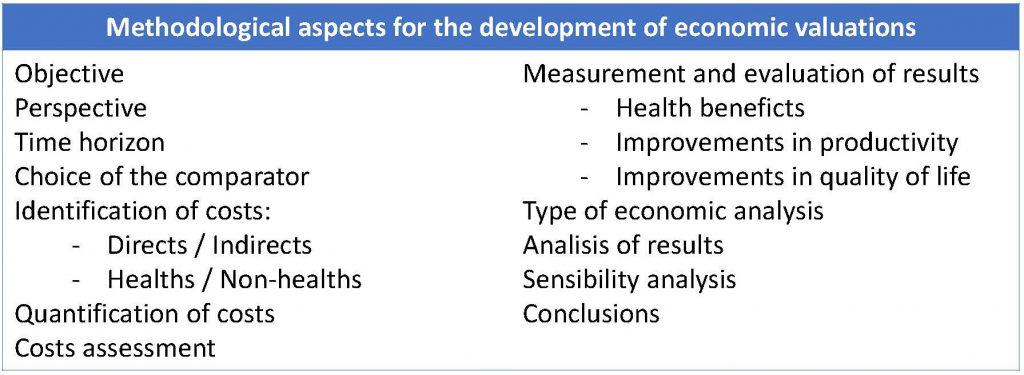

These two features are essential to say that we are facing an EV, which can be defined as the comparative analysis of different health interventions in terms of costs and benefits. The methodology of development of an EV will have to take into account a number of aspects that we list below and that you can see summarized in the attached table.

– Objective of the study. It will be determined if the use of a new technology is justified in terms of the benefits it produces. For this, a research question will be formulated with a structure similar to that of other types of epidemiological studies.

– Perspectives of the analysis. It is the point of view of the person or institution to whom the analysis is targeted, which will include the costs and benefits that must be taken into account from the positioning chosen. The most global perspective is that of the Society, although the one of the funders, that of specific organizations (for example, hospitals) or that of patients and families can also be adopted. The most usual is to adopt the perspective of the funders, sometimes accompanied by the social one. If so, both must be well differentiated.

– Time horizon of the analysis. It is the period of time during which the main economic and health effects of the intervention are evaluated.

– Choice of the comparator. It is a crucial point to be able to determine the incremental effectiveness of the new technology and on which the importance of the study for the decision makers will largely depend. In practice, the most commonly comparator is the alternative that is commonly used (the gold standard), although it can sometimes be compared with the non-treatment option, which must be justified.

– Identification of costs. Costs are usually considered taking into account the total amount of the resource consumed and the monetary value of the resource unit (you know, as the friendly hostesses of an old TV contest said: 25 responses, at 5 pesetas each, 125 pesetas).

The costs are classified as direct and indirect and as sanitary and non-sanitary. The direct ones are those clearly related to the illness (hospitalization, laboratory tests, laundry and kitchen, etc.), while the indirect refer to productivity or its loss (work functionality, mortality).

On the other hand, health costs are those related to the intervention (medicines, diagnostic tests, etc.), while non-health costs are those that the patient or other entities have to pay or those related to productivity.

What costs will be included in an EV? It will depend on the intervention being analyzed and, especially, on the perspective and time horizon of the analysis.

– Quantification of costs. It will be necessary to determine the amount of resources used, either individually or in aggregate, depending on the information available.

– Cost assessment. They will be assigned a unit price, specifying the source and the method used to assign this price. When the study covers long periods of time, it must be borne in mind that things do not cost the same over the years.

If I tell you that I knew a time when you went out at night with a thousand pesetas (the equivalent of about 6 euros now) and came back home with money in your pocket, you will think it is another of my frequent ravings, but I swear it is true.

To take this into account, a weighting factor or discount rate is used, which is usually between 3% and 6%. For who is curious, the general formula is CV = FV / (1 + d) n, where CV is the current value, FV future value, n is the number of years and d the discount rate.

– Identification, measurement and evaluation of results. The benefits obtained can be classified into health and non-health ones. Health benefits are clinical consequences of the intervention, generally measured from a point of view of interest to the patient (improvement of blood pressure figures, deaths avoided, etc.). On the other hand, the non-health ones are divided as they cause improvements in productivity or in the quality of life.

The first ones are easy to understand: productivity can improve because people go to work earlier (shorter hospitalization, shorter convalescence) or because they work better to improve the health conditions of the worker. The second ones are related to the concept of quality of life related to health, which reflects the impact of the disease and its treatment on the patient.

The quality of life related to health can be estimated using a series of questionnaires on the preferences of patients, summarized in a single score value that, together with the amount of life, will provide us with the quality-adjusted life year (QALY).

To assess the quality of life we refer to the utilities of the health states, which are expressed with a numerical value between 0 and 1, in which 0 represents the utility of the state of death and 1 that of perfect health. In this sense, a year of life lived in perfect health is equivalent to 1 QALY (1 year of life x 1 utility = 1 QALY).

Thus, to determine the value in QALYs we will multiply the value associated with a state of health by the years lived in that state. For example, half a year in perfect health (0.5 years x 1 utility) would be equivalent to one year with some ailments (1 year x 0.5 utility).

– Type of economic analysis. We can choose between four types of economic analysis.

The first, the cost minimization analysis. This is used when there is no difference in effect between the two options compared, situation in which will be enough to compare the costs to choose the cheapest.

The second, the cost-effectiveness analysis. This is used when the interventions are similar and determines the relationship between costs and consequences of interventions in units usually used in clinical practice (decrease in days of admission, for example).

The third, the cost-utility analysis. It is similar to cost-effectiveness, but the effectiveness is adjusted for quality of life, so the outcome is the QALY. Finally, the fourth method is the cost-benefit analysis. In this type everything is measured in monetary units, which we usually understand quite well, although it can be a little complicated to explain with them the gains in health.

– Analysis of results. The analysis will depend on the type of economic analysis used. In the case of cost-effectiveness studies, it is typical to calculate two measures, the average cost-effectiveness (dividing the cost between the benefit) and the incremental cost-effectiveness (the extra cost per unit of additional benefit obtained with an option with respect to the other).

This last parameter is important, since it constitutes a limit of efficiency of the intervention, which we will be chosen or not depending on how much we are willing to pay for an additional unit of effectiveness.

– Sensitivity analysis. As with other types of designs, EVs do not get rid off uncertainty, generally due to lack of reliability of the available data. Therefore, it is convenient to evaluate the degree of uncertainty through a sensitivity analysis to check the degree of stability of the results and how they can be modified if the main variables vary. An example may be the variation of the discount rate chosen.

There are five types of sensitivity analysis: univariate (the study variables are modified one by one), multivariate (two or more are modified), extremes (we put ourselves in the most optimistic and most pessimistic scenarios for the intervention), threshold (identifies if there is a critical value above or below which the choice is reversed towards one or the other the interventions compared) and probabilistic (assuming a certain probability distribution for the uncertainty of the parameters used).

– Conclusion. This is the last section of the development of an EV. The conclusions should take into account two aspects: internal validity (correct analysis for patients included in the study) and external validity (possibility of extrapolating the conclusions to other groups of similar patients).

As we said at the beginning of this post, EVs have a lot of jargon and its own methodological aspects, which makes it difficult for us to make a critical appraising and a correct understanding of its content. But let no one get discouraged, we can do it by relying on our three basic pillars: validity, relevance and applicability.

Critical appraisal of economic valuations

There are multiple guides that systematically explain how to assess an EV. Perhaps the first to appear was that of the British NICE (National Institute for Clinical Excellence), but subsequently others have arisen such as that of the Australian PBAC (Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee) and that of the Canadian CADTH (Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health).

In Spain we could not be less and the Laín Entralgo’s Health Technology Assessment Unit also developed an instrument to determine the quality of an EV. This guide establishes recommendations for 17 domains that closely resemble what we have said so far, completing with a checklist to facilitate the assessment of the quality of the EV.

Anyway, as my usual sufferers know, I prefer to use a simpler checklist that is available on the Internet for free, which is none other than the tool provided by the CASP group and that you can download from their website. We are going to follow these 11 CASPe’s questions, although without losing sight of the recommendations of the Spanish guide that we have mentioned.

As always, we will start with the VALIDITY, trying to answer first two elimination questions. If the answer is negative, we can leave the study aside and dedicate ourselves to another more productive task.

Is the question or objective of the evaluation well defined? The research question should be clear and define the target population of the study. There will also be three fundamental aspects that should be clear in the objective: the options compared, the perspective of the analysis and the time horizon.

Is there a sufficient description of all possible alternatives and their consequences? The actions to follow must be perfectly defined in all the compared options, including who, where and to whom each action is applied. The usual will be to compare the new technology, at least, with the one of habitual use, always justifying the choice of the comparison technology, especially if this is the non-treatment one (in the case of pharmacological interventions).

If we have been able to answer these two questions affirmatively, we will move on to the four questions of detail. Are there evidence of the effectiveness, of the intervention or of the evaluated program? We will see if there are trials, reviews or other previous studies that prove the effectiveness of the interventions. Think of a cost minimization study, in which we want to know which of the two options, both effective, is cheaper. Logically, we will have to have prior evidence of this effectiveness.

Are the effects of the intervention (or interventions) identified, measured and appropriately valued or considered? These effects can be measured with simple units, often derived from clinical practice, with monetary units and more elaborate calculation units, such as the QALYs mentioned above.

Are the costs incurred by the intervention (interventions) identified, measured and appropriately valued? The resources used must be well identified and measured in the appropriate units. The method and source used to assign the value to the resources used must be specified, as we have already mentioned. Finally, were discount rates applied to the costs of the intervention/s? And to the effects? As we already know, this is fundamental when the time horizon of the study is prolonged. In Spain, it is recommended to use a discount rate of 3% for basic resources. When doing sensitivity analysis this rate will be tested between 0% and 5%, which will allow comparison with other studies.

Once assessed the internal validity of our EV, we will answer the questions regarding the RELEVANCE of the results. Firstly, what are the evaluation results? We will review the units that have been used (QALYs, monetary costs, etc.) and if the incremental benefits analysis have been carried out, in appropriate cases.

The second question in this section refers to whether an adequate sensitivity analysis has been carried out to know how the results would vary with changes in costs or effectiveness. In addition, it is recommended that the authors justify the modifications made with respect to the base case, the choice of the variables that are modified and the method used in the sensitivity analysis.

Our Spanish guide recommends carrying out, whenever possible, a probabilistic sensitivity analysis, detailing all the statistical tests performed and the confidence intervals of the results.

Finally, we will assess the Cost-efeor external validity of our study by answering the last three questions. Would the program be equally effective in your environment? It will be necessary to consider if the target population, the perspective, the availability of technologies, etc., are applicable to our clinical context.

Finally, we must reflect on whether the costs would be transferable to our environment and if it would be worth applying them to our environment. This may depend on social, political, economic, population, etc. differences, between our environment and that in which the study has been carried out.

We’re leaving…

And with this we are going to finish this post for today. Even if I blow your mind after all we have said, you can believe me if I tell you that we have done nothing but scratch the surface of this stormy world of economic valuation studies.

We have not discussed anything, for example, about the statistical methods that can be used in studies of sensitivity, which can become complicated, nor about the studies using modeling, employing techniques only available to privileged minds, like Markov chains, stochastic models or discrete event simulation models, to name a few. Neither have we talked about the type of studies on which economic evaluations are based.

These can be experimental or observational studies, but they have a series of peculiarities that differentiate them from other studies of similar design, but with different functions. This is the case of clinical trials that incorporate an economic evaluation (also known as piggy -back clinical trials , which tend to have a more pragmatic design than conventional trials. But that is another story…